Mountain goat hunter’s ‘perfect’ experience

Published 6:00 pm Monday, December 23, 2024

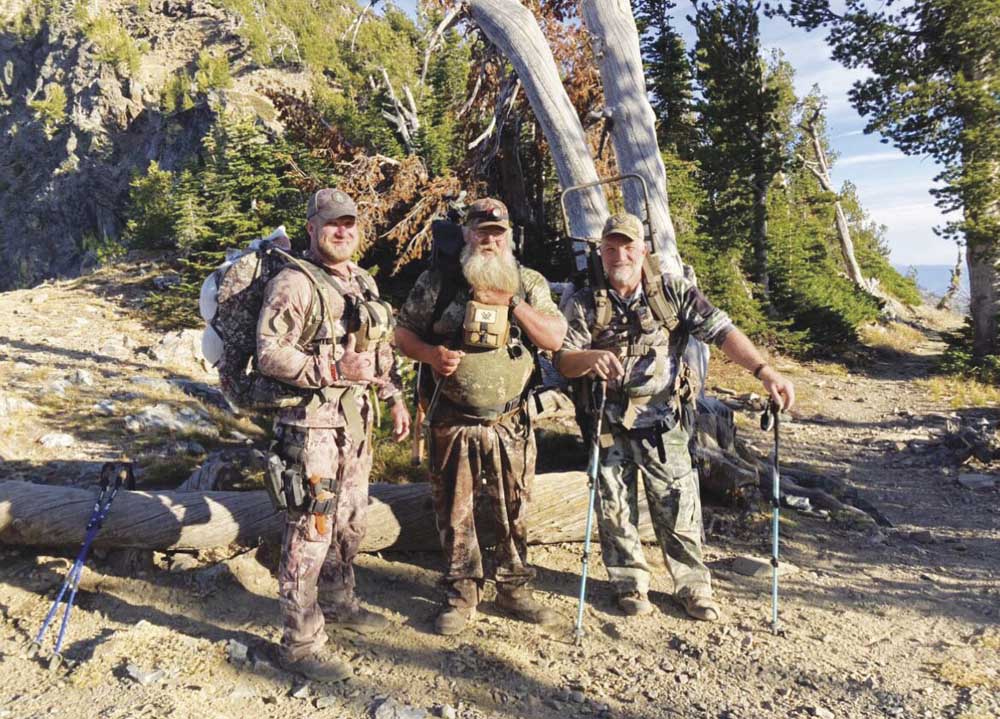

- Melissa Hamman had help hauling her mountain goat out of the Elkhorn Mountains. From left, Tyler Moothart, Melissa’s husband, Robert Hamman, and Tyler’s dad, Jim Moothart.

BAKER CITY — Melissa Hamman was watching mountain goats hundreds of yards away, not knowing that her goat was just around the next bend in the trail.

Her husband, Robert, who was just ahead of Melissa, saw the billy first.

Robert stopped so suddenly that Melissa bumped into his back.

“He whispered, ‘There’s a goat in the trail,’” Melissa said.

As she peered around Robert she too saw the goat, about 30 yards away.

Its front hooves were set on the only flat spot in sight — the rocky surface of the Elkhorn Crest National Recreation Trail about 4 miles north of Marble Creek Pass.

The billy’s rear hooves were perched on the steep slope that plunges from the trail to the glacier-carved basin that holds Twin Lakes.

On this sunny late morning of Oct. 10 the lakes glittered in the autumn sunshine, a deeper blue than the sky.

Robert crept behind Melissa.

He handed her the .308 rifle, bought just for this once-in-a-lifetime hunt.

Although she had been thinking about this moment for months, Melissa was ambivalent.

The billy was so close.

So, well, accommodating.

Robert whispered again: “Shoot him.”

Melissa whispered back: “He’s looking at me.”

Robert: “I know. Shoot him.”

Melissa squeezed the trigger.

The bullet flew true.

The billy tumbled down the slope.

Melissa fired four more times, but the final bullet, she said, wasn’t really necessary.

But she knew mountain goats were tough to bring down.

The billy, after presenting the perfect target, landed in an equally ideal spot.

“He slowly rolled right onto the trail,” Melissa said.

The trail, in this case, is the path that intersects the Elkhorn Crest Trail in a saddle and switchbacks down to Twin Lakes.

She shot the goat just south of the saddle.

Just as dusk was falling, Melissa and her husband, along with friends Jim Moothart and his son, Tyler, who offered to help haul the meat, horns and hide, trudged along the final section of the trail and arrived at Marble Creek Pass.

She was exhausted.

But exhilarated.

“The whole day to me was absolutely perfect,” she said. “Better than I ever anticipated.”

The longest odds

It was also an experience Melissa never expected to have.

Most hunters don’t.

The odds are daunting.

Melissa was one of about 1,700 people who applied for one of three tags to hunt mountain goats in the Elkhorn Mountains during October 2024.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife issued 21 mountain goat tags this year, nine of those for the Elkhorns. There are three monthlong hunts, each with three tags — August, September and October.

A goat tag is the rarest of big-game hunting opportunities in Oregon. And as with bighorn sheep tags, hunters can draw only one in a lifetime.

Melissa, who is a Baker City native, has been an avid hunter since she and Robert were married 21 years ago.

She said she applies every year for a mountain goat tag, more out of habit than with any realistic hope of getting one.

“I just cross my fingers,” she said with a laugh.

This year, when the tag results were unveiled in June, Robert, who owns a custom spraying business, was working in John Day.

Melissa, who is a drug and alcohol counselor, was in Baker City.

Robert called her about 9 p.m. He said he was having trouble accessing the tag results and asked her to check.

Melissa admits she was a trifle annoyed.

But she wasn’t suspicious when Robert suggested that she check on her applications first.

As the results appeared on the computer screen, she read them.

“I got a deer, goat, and elk,” Melissa said.

Robert asked her to repeat the list.

She did.

“Are you listening to what you’re saying?” Robert asked.

Only then did Melissa realize that between the two common tags, for deer and elk hunts, she had said “goat.”

Robert, whose prank had not gone exactly as planned, told his wife that “I figured you’d be more excited.”

He explained the genesis of the joke.

While working in John Day he was approached by someone from Baker City who had access to the list of mountain goat tag recipients.

The man saw the name “Hamman” painted on the side of Robert’s work truck. He asked Robert if he was related to Melissa Hamman.

Having learned that Melissa had drawn a goat tag, Robert decided that rather than just tell her the exciting news, he would entice her to find out herself and then revel in her reaction.

“He thoroughly enjoyed fooling me,” she said.

In reality, Melissa said, it wasn’t until the middle of that night, when she awoke, that she truly acknowledged how unlikely her situation was.

Then she started to get nervous.

“What if I don’t get (a goat)?” she pondered.

Melissa said friends assured her that she would see plenty of goats.

She knew that in theory they were right.

The Elkhorns harbor one of Oregon’s biggest, and healthiest, herds of mountain goats.

Only the nearby Wallowas rival the Elkhorns in that regard.

Since ODFW released 21 goats in the Pine Creek drainage from 1983-86 (the animals were trapped in Idaho, Alaska and Washington and trucked to the Elkhorns), the goats have thrived. In some years the population has topped 350, according to aerial and ground surveys.

Goats have been prolific enough in the Elkhorns to serve as the seed stock for, among other newly established herds, ones in Hells Canyon, the Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness in Union County, the Strawberry Mountains south of Prairie City, and the Mount Jefferson region in the central Cascades of Oregon.

Over the first 15 years or so of the 21st century, ODFW used an overhead net to capture more than 130 goats near Goodrich Reservoir, in the Baker City watershed, and transplanted them in other ranges.

But Melissa was still nervous.

Tough terrain

Although goats are plentiful in the Elkhorns, the terrain poses a considerable challenge.

“I knew it was going to be a tough hunt,” Melissa said.

She applied for the October hunt, rather than August or September, because she figured goats would have thicker wool by autumn. The animals, unlike deer and elk, don’t migrate to lower elevations during winter and are able to survive the polar conditions above 7,000 feet.

Melissa said she understood the potential risk of early storms plastering the Elkhorns in deep snow.

But since she never anticipated drawing a tag, that concern was more hypothetical than real.

Due to work schedules, the Hammans weren’t able to start hunting until Oct. 6, a Sunday.

They hiked on the Elkhorn Crest Trail to Twin Lakes.

They saw some goats, but no mature billies.

Although hunters can legally shoot any goat, ODFW recommends hunters target billies. Research in the Wallowas in the 1960s and 1970s, when hunting was allowed, showed that when hunters killed nannies, which teach their offspring how to survive, it had deleterious effects on the goat population.

If there is a nexus for mountain goats in Oregon, it is Twin Lakes.

Goats there are both numerous and, because they are hunted so rarely, they have little fear of people and will graze within feet of backpackers’ tents. ODFW biologists said the goats, which crave salt, are also attracted by hikers’ sweat-soaked trekking pole handles, socks and other salt-encrusted items.

After resting on Oct. 7, the Hammans rode their four-wheeler on Oct. 8 to Cracker Saddle, above Bourne, and hiked to Summit Lake.

Although they didn’t see any goats, they “just enjoyed listening to nothing and looking at the lake,” Melissa said.

Two days later, on Oct. 10, the couple returned to Marble Creek Pass and their rendezvous with the billy.

During the hike north on the Elkhorn Crest Trail, Melissa said she spotted several goats, none close together, on the precipitous slopes above upper Twin Lake, their white coats conspicuous against the dark brown sedimentary rocks.

When she suggested to Robert that those were likely billies, which are often solitary, his response, since he knew how torturous the terrain was and how far from the trail the goats were, was succinct: “Good luck going and getting one there.”

Not long after, the billy standing partially in the trail made that prospect unnecessary.

A ‘perfect’ experience

Melissa said she quickly decided what to do with the billy.

She enlisted a taxidermist from Vale to prepare a full body mount of the animal.

“I’m never going to get this chance again,” she said.

Melissa said ODFW biologists, who examine all mountain goats taken by hunters, estimated the billy’s age as 5 to 6 years old. His sharp black horns are about 8½ inches long, and just 1/8th of an inch from being perfectly symmetrical.

Not that Melissa is concerned about fractions of an inch.

“I just think he’s perfect,” she said of the billy.

Melissa said she and Robert have enjoyed the goat steaks.

“The meat has a different taste,” she said. “It’s not gamey, but you can tell you’re eating wild meat.”

She said they had some of the meat made into hamburger.

Melissa said the entire experience exceeded her expectations — which she admits were probably unfairly high because the opportunity was singular.

The goat is the second big game animal she has killed.

The first was a doe deer, several years ago.

Although she squeezed the trigger, Melissa said she might not have been the person most excited in that moment in the brilliant early autumn sunshine above 8,000 feet.

“My husband was literally jumping up and down after the first shot,” she said.

Even though she had exacted a bit of revenge after Robert’s prank back in June when the tag results came in.

“He’s a little jealous,” Melissa said with a laugh.

Mountain goats in Oregon

Most of Oregon’s mountain goats live in the Elkhorn or Wallowa mountains.

There are smaller populations in the Strawberry Mountains south of Prairie City, in Hells Canyon, in the Wenaha unit of northern Union and Wallowa counties, and in the Cascade Mountains near Mount Jefferson. There’s also a frequently visible herd in the Perry area along Interstate 84 just west of La Grande.

“The whole day to me was absolutely perfect. Better than I ever anticipated.”

— Melissa Hamman, who killed a mountain goat on Oct. 10, 2024, in the Elkhorn Mountains west of Baker City