COLUMN: Measure 118 brought Oregonians together — to say no to a new tax

Published 8:06 am Tuesday, November 12, 2024

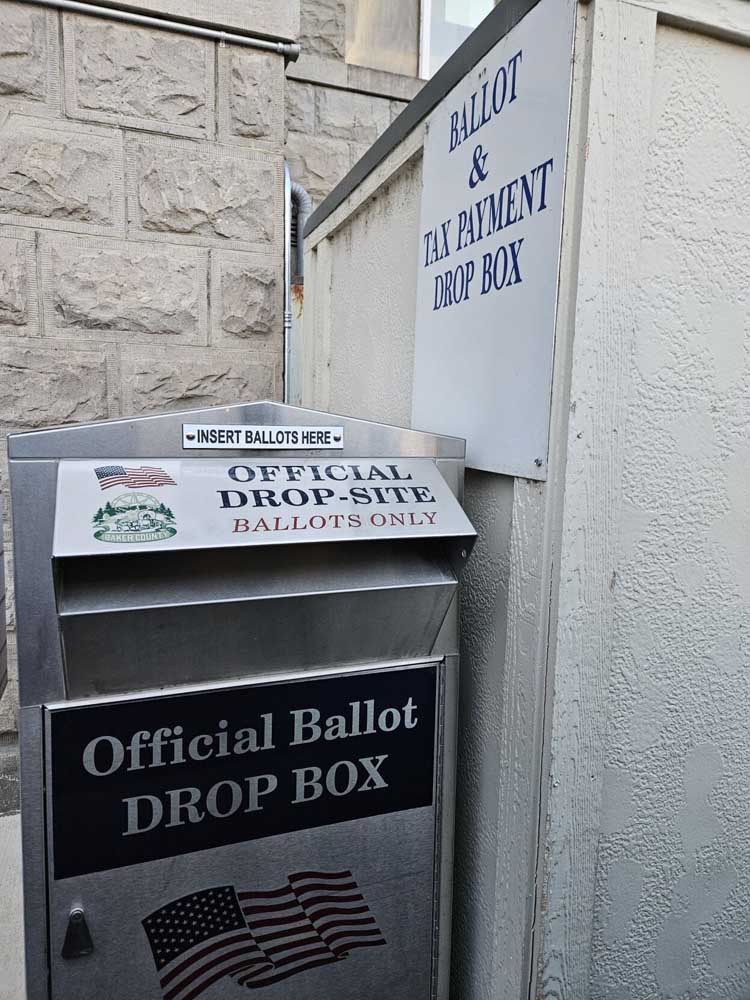

- Voters can return their ballots to this box on the west (Fourth Street) side of the Baker County Courthouse at any time up to 8 p.m. on Nov. 5, 2024.

The campaign promoting Oregon’s Measure 118 on the Nov. 5 ballot, which would have imposed a new corporate tax to give residents a $1,600 annual payment, failed mightily in one respect but succeeded in another.

These contrasting results were not coincidental.

Indeed, the success happened only because the measure took such a thorough whipping by the electorate.

Measure 118 stands out for two related reasons.

First, it is a rare example of voters in Northeastern Oregon (and other rural regions) agreeing with their counterparts in the metropolitan counties where most voters live.

But what surprised me most isn’t that a majority of voters in each of the state’s 36 counties rejected the measure, which could have exacerbated the inflation that has plagued the country over the past few years.

I was stunned because the measure was nearly as unpopular in the Portland metro area as it was in the hinterlands.

Examples of electoral unanimity are rare in Oregon.

The Cascade Mountains, which divide the state into quite dissimilar climatic regions, stand as a political barrier as well.

When it comes to weather, the mountains’ effect has a straightforward scientific explanation.

Moisture-laden storms that sweep into Oregon from the North Pacific expectorate most of their liquid load when they climb the Cascades. The air cools as it rises, and the colder the air the less moisture it can hold in vapor form — which is to say, clouds.

Once the air has crossed the Cascade crest it has dropped much of its moisture as rain or snow. As the air descends the east slopes it warms, which means it can keep most of its shrunken volume of water.

The considerable rain shadow cast by the Cascades is responsible for the dramatic difference in vegetation between the west and east sides. The transition from the lush rainforests to the arid sagebrush steppe is stark, in places happening over a span of 10 or fewer miles.

The mountains aren’t directly responsible, of course, for the political divide.

Nor is that divide anything like as distinct as the geographic one.

Oregon’s political chasm is better described as urban versus rural.

Even in ostensibly urban counties in the Portland area, such as Clackamas and Washington, residents in rural precincts tend to vote much as their counterparts do in Eastern Oregon.

But these rural voters, who as a rule favor Republican candidates and conservative issues, are a minority.

The differences are most obvious in races such as the presidential campaign.

Statewide, the Kamala Harris/Tim Walz ticket garnered 55% of votes.

The Democratic duo got a majority of votes in just nine of the 36 counties, but that list includes each of the top four counties in population — Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas and Lane. Those four counties are home to 52% of Oregon’s nearly 4.3 million residents.

But even among those four counties there are substantial differences, electorally speaking.

Multnomah, the most populous and by far the most urban, is also the most reliably Democratic county. Harris/Walz polled almost 79% in Multnomah, which has almost 20% of Oregon’s nearly 3 million registered voters. Benton County, with nearly 68% supporting the Democratic ticket, was a distant second in its preference for the Democrats.

The urban-rural difference is more conspicuous in Clackamas and Lane counties, both of which are much less urban than Multnomah. Harris/Walz got 53% of the votes in Clackamas County, 59% in Lane.

Republicans Donald Trump and JD Vance won every county east of the Cascades except Deschutes.

But the GOP ticket wasn’t as popular in most of those predominantly rural counties as Harris/Walz were in Multnomah County.

Trump/Vance won a higher percentage than the Democrats’ 78.6% in Multnomah County in only one county — Lake, at 81.3%.

In Northeastern Oregon the GOP pair won every county handily, including 73% in Baker County and 78.5% in Grant County.

But enough about the yawning differences among Oregon’s electorate.

Let’s look at Measure 118.

Voters hated it.

Everywhere they hated it.

The measure failed spectacularly in all 36 counties.

Statewide it went down 78% to 22%.

What surprised me most, though, was that the level of voter disdain for the measure didn’t vary much, even between counties or regions where the difference elsewhere on the ballot was comparatively huge.

At a county level, opposition to Measure 118 ranged from a high of 89.3% in Sherman County to a low of 72.9% in Multnomah.

The predilections of Multnomah and the three other most populous counties — Washington, Clackamas and Lane — showed up in the Measure 118 tallies. But barely — the gap was tiny compared with results from the presidential race.

In Multnomah, for instance, voters rejected the measure at only a slightly lower rate than statewide — 72.9% in the county compared with 78% overall.

But in the presidential race, Multnomah voters favored Harris/Walz at a 78.6% clip, far above the statewide result of 55%.

The difference is greater still when comparing Multnomah with most rural counties.

In Baker County, for instance, 86.1% of voters opposed Measure 118. That’s 13.2 percentage points higher than in Multnomah County.

Yet in the presidential race, the preference for Harris/Walz was 78.6% in Multnomah County, and 24% in Baker County — a difference of 54.6 percentage points, more than four times as wide as the margin for Measure 118.

Measure 118 is an electoral anomaly, to be sure.

I’m certain that statewide abhorrence for the measure does not portend a trend toward something approaching unanimity among Oregon voters.

The presidential race results show how farfetched that notion is.

But there are topics that most Oregon voters agree on.