Essay: Eastern Oregon water pollution is a story of divides

Published 7:00 am Thursday, December 22, 2022

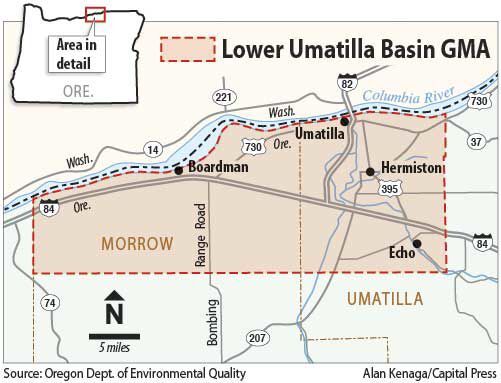

- Lower Umatilla GMA

Imagine going to the sink to fill your coffee pot. Maybe you stare out the window while the pot fills, looking out over the landscape or just thinking morning thoughts.

You probably don’t think about the convenience and miracle of flowing water. You probably don’t wonder if the water is safe.

For the last 30 years, most people in the Lower Umatilla Basin of eastern Oregon were like you — sleepily making coffee and thinking about their days, their families, their problems.

But now standing at the sink folks must make worried choices. Can I drink this? Is it OK to wash dishes? Did this water give my neighbor cancer? Is my filter working? People are anxious, angry and fed up because their water is not safe and it hasn’t been for decades, they didn’t know it, and they were not told.

They have been drinking and cooking with this water, watching their kids drink out of the hose on hot days, all without knowing the risk.

In June 2022 Morrow County declared a water emergency due to high levels of nitrate found in private drinking water wells.

The standard for nitrate under the federal Safe Drinking Water Act is 10 milligrams per liter or less, but in many wells in the Lower Umatilla Basin it is three, four and five times the standard. Nitrates are tasteless, odorless, invisible pollutants that cause “blue baby syndrome” and are linked to miscarriage, thyroid disease, and cancers. In infants and pregnant people, the danger is high and near term.

For most adults, the damage is done over time.

In so many ways, this story is a story of divides — between urban and rural, between economic classes, and between the government and the people.

We can see the rural-urban divide in the differences in concern and protection for rural vs urban people.

For people living inside the small towns of the Lower Umatilla Basin — Hermiston, Umatilla, Boardman, Irrigon, Stanfield and Echo — drinking water is tested, monitored, and treated or “blended” until it meets the federal Safe Drinking Water standard. But the Safe Drinking Water Act does not apply to private domestic wells, leaving the most rural and isolated households without protection or recourse.

This begs the question — why would we make laws that treat rural and urban people differently? If safe water is a human right and basic need, why has the state of Oregon shirked its duty to rural people for so long?

Class division is clear in terms of who is polluting and who is impacted by the pollution.

The nitrate is coming from mega agriculture and industry including food processors that have made Morrow County the one of the wealthiest counties in the state. In terms of assessed market value, the county is worth $4-5 billion.

Big business in the county also means there are a lot of high-income corporate earners. These are the folks who are making decisions that can increase or decrease nitrate levels in the groundwater. On the other hand, the people most affected by nitrate are average middle- and low-income people — many of whom work in the fields, dairies, and factories that are responsible for the pollution.

The divide between the government and the people shows up in the historic lack of urgency, responsiveness or even simple information sharing by state and local governments.

In 1990 the state designated Lower Umatilla Basin a critical groundwater area. For the last 30 years an alphabet soup of agencies has been collecting data, discussing the problem, and taking little action to either stop the pollution or inform the public about the danger.

When Morrow County Public Health and Oregon Rural Action, a local community organization I work for, began doing door-to-door outreach and water testing in June, we found that most people had a vague idea that the water was “bad.” Some people were drinking it, most people were cooking with it, and some were even boiling it, thinking this would fix the problem. However, boiling and cooking with the water concentrates nitrate and makes the water more dangerous.

State and local government have known about the problem and did not do basic public education over the last 30 years.

Most of the people we have talked to have lived in the area for decades but had never been given information on the nitrate situation — in English, Spanish or in any of the other languages spoken in the basin. What diseases, health problems, and suffering could have been prevented in this time if people had known not to drink the water?

Since the door-to-door testing in Morrow County, the issue has become more widely known. The Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has fined industrial polluters millions of dollars for thousands of permit violations. But DEQ also just approved a modified permit that allows the Port of Morrow to continue “winter application” of polluted water on fields for another years, a practice that we have known for decades impacts groundwater and wells.

The Oregon Health Authority (OHA) just began visiting the basin in November 2022 to plan more testing, treatment, and outreach. But the response has been too slow for the people facing the water every day.

Morrow and Umatilla counties have been testing water and working to inform the public with little state financial support to reach the 4,500 wells and almost 15,000 people who rely on them. But there is gulf in staff capacity and money.

This isn’t sustainable and it won’t meet the needs of our rural neighbors who deserve safe water.

Decisionmakers are not eager to take on this problem.

No one wants to take responsibility for the neglect and harm done to the people of the basin. No one wants to pay the full cost of the long, slow, house-by-house process of connecting rural well users to public water systems or for home treatment systems. No one wants to take on the power of the polluters because they are also the “economic engine” of the region.

The nitrate issue, as one DEQ official told me, is “the biggest mess in the state of Oregon.”

Very few of the people in government, agriculture or industry now were making decisions about nitrate in 1990. The past is not on them, but the present and future are.

People in the basin can’t wait another 30 years for solutions. People don’t want more research, more discussion, more lax regulation.

What I have heard is people saying they want action now by DEQ, OHA, the Environmental Protection Agency, their elected representatives, and the governor — by anyone and everyone who can make the water safe. As one man told me, “I’m not looking to sue anyone here. I just want safe water for my great-grandkids.”

The people of the basin understand that nitrate pollution is persistent, the problem is decades in the making, and it cannot be fixed overnight.

As local people dive into this issue, they understand the nuances, the barriers, the politics and the economic forces behind the status quo. They are experts on their communities and their own lives.

They understand that as dispersed, rural people, farm workers, small farmers, immigrants, laborers and senior citizens they were never valued enough to get protection from pollution they can’t see, didn’t create and can’t control.

But they do not accept this going forward.

This problem is complicated, but so is building a road or going to the moon. Despite the history of this problem, it is not intractable. With urgency, flexibility and creativity, we can ensure everyone affected by nitrate in the Lower Umatilla Basin can equitably access safe water.

We must face this issue head on and right now. We need decisionmakers to transform into champions. We need a lot of money for this marathon. We need the people most impacted by the pollution to be allowed to design the solutions that will work for them.

If we do this, we can bridge a lot of divides between rural and urban and between the government and the people. We can also build a bridge from pollution to safe water for all.

Nella Mae Parks is a farmer living in Cove. She is also an organizer with Oregon Rural Action working on rural issues in eastern Oregon.